The Trump administration appears not to believe in “independent” agencies. It seems to think that Congress lacks the constitutional authority to immunize agency heads from unlimited presidential removal power. With that thought in mind, the President has fired members of a variety of independent agencies, including the National Relations Board (NLRB) and the Federal Trade Commission (FTC).

If the Trump administration is right on this point, then the structure of American government will have to be significantly changed. The FCC, the FTC, the SEC, the NLRB, the Fed, the NRC, the CPSC - for better or for worse, all these, and more, will be treated like Cabinet agencies and controlled by the White House. (For an overview, see https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/full/10.1086/714860)

The constitutional legitimacy of independent agencies comes from a 1935 case, Humphrey’s Executor v. United States, where the court ruled that Congress could limit the president’s power to remove a head of the FTC — and thus that it could create independent agencies. The decision has long taken to remove constitutional doubts about the agencies mentioned above.

Still, it should be acknowledged that some recent Supreme Court decisions suggest a lot of skepticism about independent agencies, without overruling Humphrey’s Executor. (Technical note: In 1935, the FTC was understood to have limited powers, which means that the statutory provisions that make the current FTC independent, and the provisions governing many independent agencies, could be struck down without formally overruling Humphrey’s Executor.)

So let’s pose the question: Should Humphrey’s Executor be overruled OR (what is almost the same thing) be sharply cabined, in a way that effectively eliminates independent agencies?

Here are three reasons to say “no.”

The text of Article II is actually indeterminate (as Brandeis and Holmes explained long ago), and the best understanding of the founding period is that the text’s original meaning did not forbid Congress from restricting the president’s removal authority. There is a lot of recent work or recent-ish historical work in this vein. Consider Mashaw, Shugarman, Chabot. (See https://scholarship.law.nd.edu/ndlr/vol98/iss1/3/) It’s pretty devastating - more devastating than I expected - to the originalist argument against Humphrey’s Executor. (I am a big fan of Prakash, and at one point thought that his argument about the Decision of 1789, in an excellent paper in the Cornell Law Review, was convincing. But Shugarman and others show otherwise.)

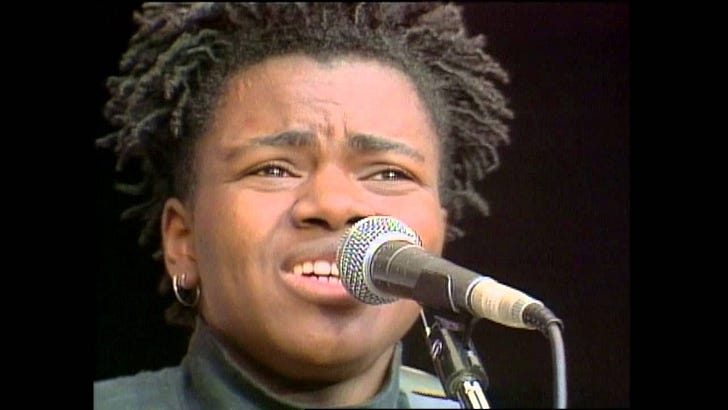

Suppose that we are Burkeans. We believe in respect for precedent and longstanding traditions and practices. Independent agencies have been thought to be legitimate for 90 years. It’s one thing to overrule Roe v. Wade; it’s quite another to say that institutions that have been part of the fabric of American government are suddenly unconstitutional, and because of a theory with a doubtful historical pedigree. Overruling Humphrey’s Executor would be a kind of revolution, by people in the grip of a theory. Speaking of which, this emphatically nonBurkean song is really good, but it’s emphatically not about overruling Humphrey’s Executor:

(a) The republic would not fall if certain independent agencies became executive agencies. Consider the National Labor Relations Board, the Federal Trade Commission, the Consumer Product Safety Commission, and the Securities and Exchange Commission. You can argue whether it’s best for one, two, or all of these to be independent agencies, but the stakes do not seem all that high. At least reasonable people could say so. (This question is worth more investigation.)

(b) But consider the Federal Reserve Board or the Federal Communications Commission (FCC). If the Fed were subject to ongoing presidential control, its functions would be compromised. Interest rates could be lowered, not because lowering them would be a terrific idea, but because lowering them would promote the political interests of the president and those whom he supports. That would be dangerous. If the FCC were subject to ongoing presidential control, the president could play favorites with the communications industry, in a way that could well distort political processes. That would be dangerous.

(c) The independence of the Fed and the FCC can be connected with core structural commitments of the Constitution, associated with the effort to restrict certain forms of self-dealing and concentration of power.

(d) If Humphrey’s Executor is overruled, some very fancy footwork would be necessary to preserve the independence of the Fed and the FCC.

In the end, the three arguments strongly argue against rejecting the long-established idea that Congress has the constitutional authority to immunize (some) agencies from plenary presidential control.

It is relevant that there are some not-really-nuclear ways to increase presidential authority over the independent agencies without overruling Humphrey’s Executor. For example, statutory restrictions on the removal power could be interpreted to allow a degree of presidential authority. (For one account, see https://www.law.georgetown.edu/georgetown-law-journal/wp-content/uploads/sites/26/2021/03/Sunstein_Vermeule_Presidential-Review-The-Presidents-Statutory-Authority-over-Independent-Agencies.pdf)

There are a lot of things that the United States needs right now. One of them is not a thunderclap, in the form of a constitutional ban, announced for the first time in the nation’s history, on independent agencies.