Originalism's Remarkable Triumph

On Justice Alito's Coming Book

1

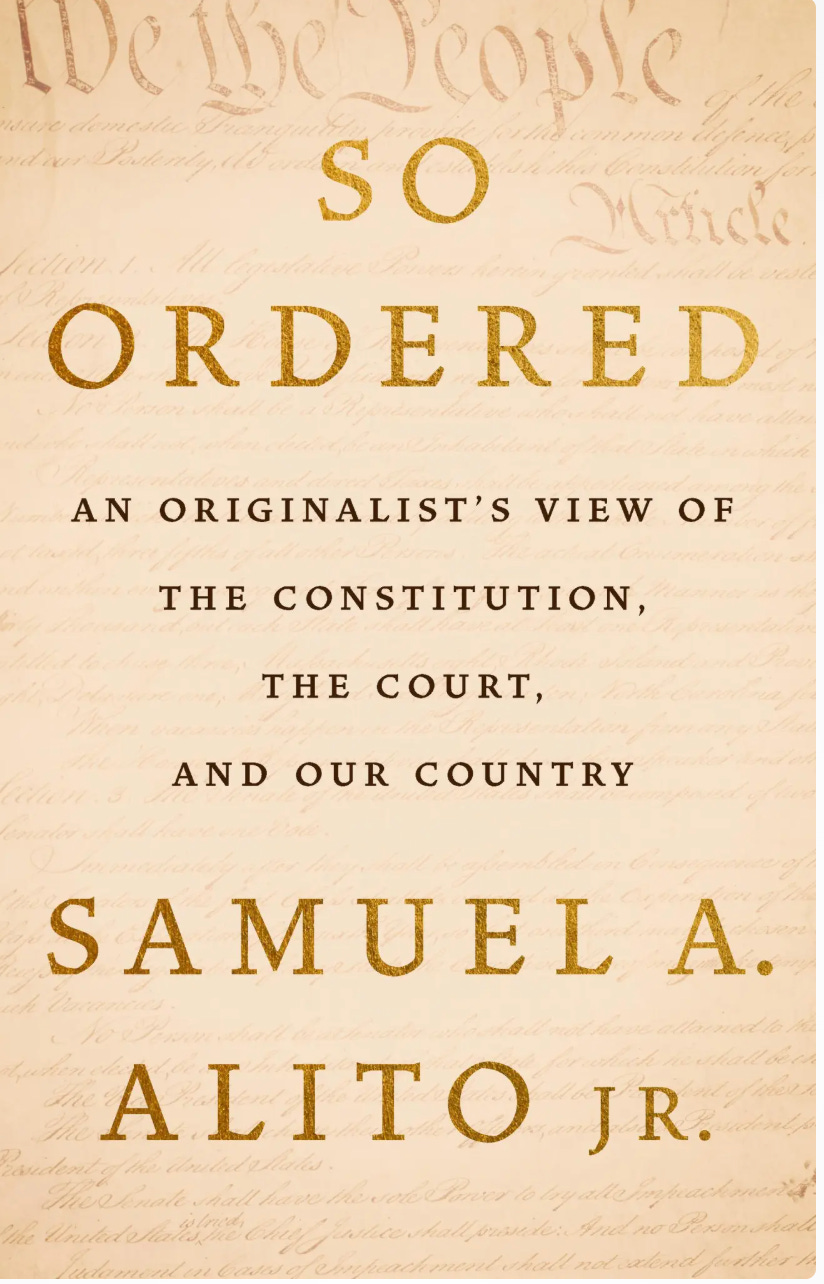

Justice Samuel Alito has a new book coming out, and the subtitle is striking:

See? It looks like an originalist manifesto. (And note well: An originalist’s view not just of the Constitution - also of our country.)

Here are some words from the publisher:

In this surprisingly personal book, he vigorously defends his “originalist” approach to the Constitution, identifies the threats to our liberties, and reflects on faith, the nature of law, and American culture.

Here’s what makes this so interesting. If you asked specialists to name originalists on the Supreme Court, Alito would not be the first they would mention, or the second, or the third, or the fourth. He might not be mentioned at all.

To be sure, he has been an important and distinctive voice on the Court. But for better or for worse, he has not been a distinctly or consistently originalist voice on the Court.

Here comes his book, with that subtitle: An Originalist’s View of the Constitution, the Court, and the Country.

Wow. What should we make of that?

2

Consider some instructive words about Justice Alito’s opinion in Dobbs, overruling Roe. v. Wade:

Although the outcome could possibly have been justified on originalist grounds, to the extent that the outcome of Dobbs is controlled by this application of Glucksberg’s nonoriginalist approach to substantive due process, it is a nonoriginalist decision in its reasoning. Indeed, the nonoriginalist nature of the Dobbs majority is suggested by Justice Thomas’s concurring opinion, which explicitly rejects the entirety of substantive due process on originalist grounds, a claim that Justice Alito does not contest.

Thus write Randy Barnett and Lawrence Solum in an illuminating recent essay on the rule of originalism in various Supreme Court opinions. (See https://scholarlycommons.law.northwestern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1541&context=nulr)

True, Barnett and Solum rightly point to originalist elements in Dobbs. But their central message is that for originalists, “Justice Alito’s opinion falls short, both because it fails to articulate the original public meaning of the clause and because it fails to examine most of the relevant evidence of such meaning.”

This is an observation. It need not be a criticism of Dobbs. Originalism was not the prevailing method of interpretation for many decades (take your pick - 1789 until 2015? 1910 until 2015? 1930 until 2015?). You might think that a nonoriginalist Dobbs was better than an originalist Dobbs. (I do.)

The only point is that Justice Alito did not write an originalist Dobbs. That should not be surprising. During his years on the Court, he has been a powerful voice, and shown a powerful mind, but no one would say that he has been a distinctly originalist voice.

3

A systematic analysis of Justice Alito’s work would be necessary, of course, to get entirely clear on the matter, but it seems fair to say:

that Justice Scalia was the most prominent exponent of originalism over the last decades;

that Justice Thomas is the most consistent originalist on the Court;

that Justice Gorsuch is also a pretty consistent originalist, and publicly committed to originalism;

that Justice Barrett is committed to originalism as well, though she is a complex thinker who departs from originalism on important occasions, partly because she generally respects precedent;

that Justice Kavanaugh likes originalism a lot, though he is also a pragmatist;

and that Justice Alito, while interested in the original public meaning, has been more broadly in the mold of Justice Harlan, who was a tradition-focused, restraint-focused, conservative dissenter on the Warren Court.

Justice Alito might have a bit more bite and edge than Justice Harlan, and they are not at all the same; but the comparison seems instructive. This is just a way of saying that if Justices Scalia and Thomas are defining originalists, Justice Alito has been more like a Burkean, focused on traditions, and not insistently committed to the original public meaning. (Take a look at his standing opinions, for example.)

4

And then there’s that subtitle: An Originalist’s View of the Constitution, the Court, and the Country. What are we to make of it? Actually I don’t know.

One possibility is that Justice Alito is a convert. He was not an originalist in (say) 2007or 2012. He is an originalist now.

Another possibility is that Justice Alito was always an originalist, but he is also a judge, not a law professor, and as a judge, he has worked within the existing materials, rather than insisting on his own preferred theory of interpretation. If so, his years as a member of the Court have been, in that sense, methodologically humble. But as solo author of a book, he is entitled to say what he really thinks, and has always thought.

(I tend to think that neither of these speculations is quite true. But I am at all not sure what is true.)

One thing is clear: As a matter of history’s arc, the subtitle is a testimony to the remarkable triumph of originalism - one of the most extraordinary developments in the entire history of American constitutional law.

After Justice Scalia died (in 2016 (not so long ago), it looked as if originalism might be dead too, a kind of historical curiosity. It would have been odd or reckless to predict that originalism would soon command a majority on the Supreme Court. It would also have been odd or reckless to predict that Justice Alito would write a book proclaiming his commitment to originalism.

But here we are.

There is a market for Originalism. Who would buy Alito's book if the subtitle were "A Burkean, Harlan-esque View of the Court, the Constitution, and Our Country"?

Alito wants the legitimacy of being an Originalist, without the constraints of Originalism.